THE FREEDOM TRAIL

Length 1.5 Miles

Type: Culture

Difficulty Level: Strenuous

Introduction

The Norwich Freedom Trail is a part of the Walk Norwich Trail system and celebrates Norwich’s rich and diverse story of African-American heritage, highlighting notable people who played important roles in the movement to end slavery and advance civil rights before and after the United States Civil War. This courageous cast of individuals including men, women, and children, ranges from freedom seekers to progressive educators and humanitarians, elected officials, and civic leaders. All found ways—some quietly, others in the public forum—to fight for liberty and human dignity in an era of social and political upheaval. Among them is, David Ruggles, who became a nationally known African-American “conductor” on the Underground Railroad. Later on others, like Sarah Harris and James L. Smith, both residents of the historically African-American community known as Jail Hill, made their own marks. Sarah Harris Fayerweather broke a barrier as the first black woman to enter one of Connecticut’s prestigious academies for privileged well-to-do young white women. A freedom seeker from Virginia, Smith became a successful Norwich shoemaker, his journey to freedom embodies the struggle of those who escaped from enslavement to make new lives in the North in the years before the Civil War.

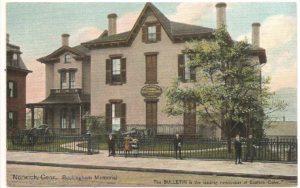

The trail also sheds light on Norwich’s connection to Abraham Lincoln, who spoke here in 1860 in support of the re-election of Connecticut Governor William A. Buckingham. Lincoln’s brilliant analysis of “the problem of slavery” presented to the nation was an important factor in his nomination as the Republican candidate for president later that year. As Connecticut’s Civil War governor, William Buckingham led the state through the turmoil of the period, supported the Emancipation Proclamation, enlisted blacks into two regiments to fight for the Union, and advocated extending the right to vote to black men. Buckingham’s historic home still stands in downtown Norwich, and he is buried in the city’s Yantic Cemetery.

The Norwich Freedom Trail focuses on sites that embody the struggle toward freedom and celebrates the accomplishments of Norwich’s African American community, and of others who helped the community at a time when anti-slavery efforts in Connecticut faced stiff, fierce and often violent opposition.

Although this tour largely concentrates on the abolitionist movement, it also touches on more modern African-American history in Norwich, including the story of folk artist Ellis Walter Ruley, and the recent work of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) Norwich Branch NAACP.

The trail, which includes a minimal amount of driving, concentrates on Jail Hill, a National Register Historic District adjacent to downtown Norwich, it then continues downtown and beyond, ending at Ellis Walter Ruley Memorial Park, Ruley’s former homestead near Route 2 East and the gravesite of Boston Trowtrow, one of three Norwich “black governors” elected from the city’s African-American community in the 1700s, located in the Norwichtown Colonial Burying Grounds. Many sites along the way are part of the Connecticut Freedom Trail, which recognizes sites significant to the state’s African-American history and culture.

Free parking can be found in several garages in downtown Norwich. Walkers take care: Jail Hill has very steep inclines in certain sections on School Street and Cedar Street. Much of the walk is along the sidewalk in the Jail Hill and the Downtown Norwich Historic District. Please be aware of traffic.

Slavery in Colonial Connecticut

In Connecticut, slavery became common as the result of the Pequot War of 1636–37. Native American captives were forced into enslavement by the colonists and exchanged for enslaved African in the West Indies. By the early to late 1700s, slavery was well established in the colony, especially in seaports such as Norwich and New London. In 1774, when the importation of enslaved individuals into the colony was banned, Norwich’s black population was 234 out of 7,327 inhabitants, the second largest in New London County. At the time of the Revolutionary War, Connecticut had the largest slave population in New England.

The colonial legislature in Connecticut passed a series of acts restricting the rights of free and enslaved blacks. Although there was no specific legislation preventing free blacks from voting, nevertheless they were denied that right throughout the colonial period. Due to the revolutionary fervor period of 1775–83, many Northern enslavers saw a contradiction between holding others in slavery bondage while fighting for their own liberty. As a result, some enslavers voluntarily freed their enslaved individuals through the legal process of manumission. Military service was another also provided a path to freedom. As a combined result, the free black population in Norwich and elsewhere in Connecticut rose substantially.

During the Federal Period, some Northern states adopted “gradual emancipation” laws, providing that children born to slaves after a certain date be emancipated at age twenty-five. Gradual emancipation, enacted in Connecticut in 1784, only freed those born after passage of the act by the state legislature. The goal was to phase out enslavement over an extended period of time. The process delayed the official end of enslavement in Connecticut until 1848, long after the practice was abolished in many other northern states. By this time, thousands of freedom seekers would attain their freedom on the Underground Railroad. While little is known of the operation of the Underground Railroad in Norwich, it is likely that white and black members of the Second Congregational Church were involved. Edmund Perkins, a white attorney and member of the church, was mentioned as the leader of the Underground Railroad in Norwich in the 1850s by an informant of Wilber H. Siebert in the 1890s.